Paying attention?

I’ve always been fascinated by personal performance and the level of organisation that supported it. Whether performing a sport, taking an exam, handing a difficult situation at work, writing a report, reading an academic paper. Why is it that sometimes these come easy and performance is great, other times it can be so hard?

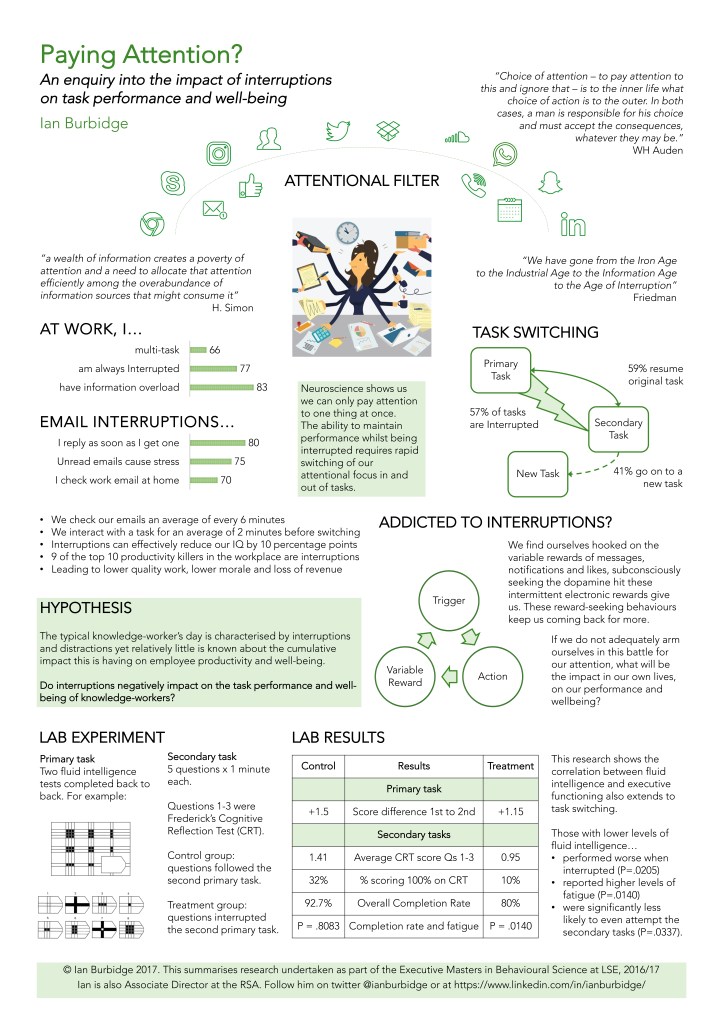

I explored these question through my master’s research where I looked at the impact of interruptions on task performance and well-being.

From archery attention…

My hours spent developing my archery skills were a great case in point and I realised the power of attention and concentration to perform well. It followed that there were things that would shatter my attention and drag it on to other things, things that didn’t serve me as I was trying to land each arrow in the centre of the target – a loud comment behind me, a sudden gust of wind, a negative thought…

On the flip side of this I also realised that organisation was important, for it was this that enabled me to get into the zone in which my attention was focused and my concentration effortless; what Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi termed flow. It required processes and tactics to help me tune out the past and the future and focus exclusively on the here-and-now. In other words, forgetting my past performance, my last arrow, regardless of where it landed on the target, and not projecting ahead to estimate my finishing position.

I realised that to more reliably enter such flow states I needed a degree of organisation. What preparation helped me enter that place of peak performance as I started my archery practice and to stay in it while I was doing it, regardless of what might happen along the way. How, in other words, would I handle the inevitable distractions and interruptions that could impair my task performance and mean that my arrow was less likely to land in the gold in the centre of the target?

…to knowledge management

Roll forwards twenty years and I’m building a career in the knowledge economy where attention is everything. It helps me read, assimilate information, develop ideas, write content, design programmes, hold deep conversations, run workshops… and so on. As in every endeavour, performance again is variable. Why is it that sometimes I would again enter a flow state, perhaps working one-on-one and really developing new and exciting concepts and ideas, and other times it felt like I was swimming in molasses, no spark, no creativity, no focus. I realised a key factor was the extent to which my attention was focused or fractured. Just as I had done years before in my archery practice.

Peak performance: How to be at your best.

Click on the link above to find out more about my practical training that will help you apply tactics and get organised so that you can operate at your best and achieve your peak performance. Benefit from my insights and research and be your best.

My research

Studying for a Masters in Behavioural Science, then, seemed to offer the perfect opportunity to develop this line of enquiry still further and practically explore the impact of interruptions on the quality of work and well-being of knowledge workers.

My research found that participants with lower levels of fluid intelligence performed worse when interrupted and reported higher levels of fatigue. In fact, they were significantly less likely to even attempt the interruption tasks. Those with high fluid intelligence performed well on all tasks and didn’t suffer any significant increase in fatigue; they were highly effective task-switchers. This has significant implications for how we organise our work and think about mental health in the workplace. Read on for more insights.

Overload

We receive information through numerous channels that compete for our attention. At work, an estimated 57% of tasks are interrupted, thereby extending the time taken to complete the task, and 41% are not even resumed after an interruption. We check our smartphones 85 times a day and our email every 6 minutes, hooked on the variable rewards of messages, notifications and likes, subconsciously seeking the dopamine hit these intermittent electronic rewards give us. Nine out of the top ten ‘productivity killers’ are interruptions. Little wonder that around a third of a knowledge-worker’s day is characterised by interruptions that necessitate task-switching.

“Calm, focused, undistracted, the linear mind is being pushed aside by a new kind of mind that wants and needs to take in and dole out information in short, disjointed, often overlapping bursts—the faster, the better”. Nicholas Carr, The Shadows

If we do not adequately arm ourselves in this battle for our attention, with the right levels of personal organisation and tactics, what will be the impact on our own performance and wellbeing?

I undertook lab research to investigate, measuring task performance on both a substantive task (a fluid intelligence test) and on a series of short tasks that formed interruptions to the substantive task. Well-being was evaluated through measures of fatigue.

Fluid and crystallised intelligence

Fluid intelligence has been shown to correlate with cognitive flexibility and executive functioning – the essential mental skills we need to get things done. The results of my experiments indicate that this correlation also extends to task switching: respondents with lower levels of fluid intelligence performed worse when interrupted and reported higher levels of fatigue. In fact, they were significantly less likely to even attempt the interruption tasks. Those with high fluid intelligence performed well on all tasks and didn’t suffer any significant increase in fatigue; they were highly effective task-switchers.

People may have high levels of crystallised intelligence, which is the ability to remember facts and apply learned experiences, but this is not related to fluid intelligence. Yet it is those with high levels of fluid intelligence – a relatively fixed commodity – that are predisposed to be better able to cope with interruptions by task-switching than others.

Task switching and mental health.

This means that those with lower levels of fluid intelligence are naturally disadvantaged in their capacity to handle interruptions in the workplace and are at a greater risk of poor wellbeing and mental health as a result.

This is a threat to our productivity as well as our health. Crucially, this is not well understood by either employers or employees as a critical driver of work-place stress.

Find out more about my Peak Performance masterclass.

Contact me if you would like more information about my research.